Stourbridge Old Town Gasworks

Be it the edge of a dual carriageway, nestled amongst residential estates, or right in the centre of a busy town, many of the sights that make up the Black Country UNESCO Geopark don’t conform to the traditional expectation of a geological site. In many ways that nonconformity is the beauty of our Geopark. Evidence for Earth’s history isn’t exclusive to cliffs, mountains or remote rural locations – it exists beneath and around us at all times, even in major urban areas. This particular window in Earth history sits just outside of the Stourbridge ring road.

Most of the Black Country’s surface geology was laid down between the Silurian and the Triassic periods, roughly 440-200 million years ago. Covering the surface in some areas though, we find evidence of a much more recent age – the mushy superficial sediment or ‘drift’ that hasn’t yet turned into rock. The nature of this mush varies in different places. In the north-western corner of the region we can find material left behind by glaciers emanating from kilometre-thick ice caps in Scotland and Wales during the last glacial period. Elsewhere the sediment originates from existing rivers and streams. The Smestow, Tame and Stour all define distinctive ‘alluvium’ deposits. But only at this Geosite, Stourbridge Old Town Gasworks, do we find river deposits predating the most recent ice age – the last interglacial period.

Most of the Black Country’s surface geology was laid down between the Silurian and the Triassic periods, roughly 440-200 million years ago. Covering the surface in some areas though, we find evidence of a much more recent age – the mushy superficial sediment or ‘drift’ that hasn’t yet turned into rock. The nature of this mush varies in different places. In the north-western corner of the region we can find material left behind by glaciers emanating from kilometre-thick ice caps in Scotland and Wales during the last glacial period. Elsewhere the sediment originates from existing rivers and streams. The Smestow, Tame and Stour all define distinctive ‘alluvium’ deposits. But only at this Geosite, Stourbridge Old Town Gasworks, do we find river deposits predating the most recent ice age – the last interglacial period.

I’ll be blunt with you: this Geosite isn’t much to look at. If you should venture to the back of the Trefoil Gardens estate during the winter when the vegetation has died back, you will see a tall orange rock face with a slightly darker loose cap of sediment. At ground level we have the Wildmoor Sandstone, which was laid down in a vast desert in the heart of the Pangaean supercontinent 250 million years ago. Atop the sandstone is our horizon of interest. This is the Stour’s ancient river terrace – preserved as it was 100,000 years ago.

These interglacial sands date from a brief warm respite in the otherwise frigid prevailing conditions of the Pleistocene. Because of the Earth’s cyclical dance through space, Earth’s climate over the last 2 million years has regularly fluctuated between lengthy, frozen ‘glacials’; and shorter, warm ‘interglacials’. Some of those warm periods, including the most recent interglacial, are of particular interest to researchers such as myself, who seek out potential analogues for how the Earth will look in the near future as a result of anthropogenic warming, and how ecosystems may respond and adapt to those changes.

So what do we know of interglacial Stourbridge? These sands were extensively quarried during the 19th and early 20th centuries and quarry workers often came across animal bones entombed within sediment. Thanks to a 1917 article by a Professor Boulton of the University of Birmingham, this knowledge has survived even though many of the original samples have subsequently been lost.

So what do we know of interglacial Stourbridge? These sands were extensively quarried during the 19th and early 20th centuries and quarry workers often came across animal bones entombed within sediment. Thanks to a 1917 article by a Professor Boulton of the University of Birmingham, this knowledge has survived even though many of the original samples have subsequently been lost.

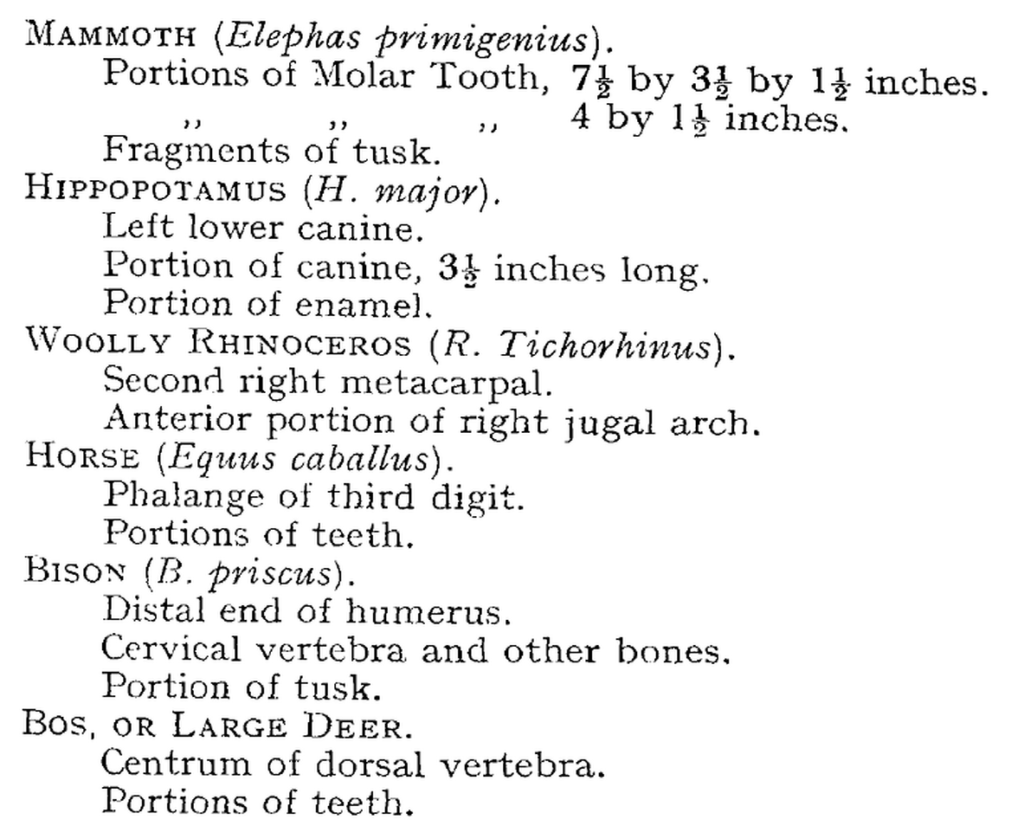

Hippos, mammoths, bison and woolly rhinos were all amongst the inhabitants of prehistoric Stourbridge. It seems likely that the remains of cold-adapted species listed here were reworked into the interglacial sediment, whilst the warm-adapted species were present through the warmer period. Hippo remains are a particularly exciting find, being exceptionally rare this far north in Europe during the Pleistocene. Apparently they must have migrated up long-extinct rivers that connected Britain and continental Europe at the time. Their presence also exhibits the relative warmth that must have persisted here at least during the summer months.

Such a menagerie of megafauna seems at odds with what we tend to think of as the ‘natural’ state of British wildlife, but it’s likely that many warm-adapted giants would have reached our shores since the close of the last ice age if it weren’t for hunting by ancient humans. The booming population of Homo Sapiens at the close of the last glacial period is almost certainly connected to a simultaneous global decline in megafauna. Apparently our ancestors’ appetites were at odds with the reproductive rate of many Pleistocene megafauna, or else we might have hippos in the Stour even today.

This Geosite’s name betrays its original purpose. In the 1830s the land adjacent to the site was turned into an enormous gas processing facility. Coal was brought in by canal and later by railway, the site conveniently being at the junction of both, where it would be converted into gas. Enormous gas holders stored it until needed, at which point it was piped away for both domestic and industrial uses in the local area. Locals might remember a successor gas holder that survived on the site until 2007. Sentimentality was apparently absent when two centuries of gas holder history came to an end, with the Stourbridge News quoting a local resident: “It is wonderful it is going as it cast[s] such a shadow over the area”. History failed to record the impression of 19th century Stourbridgians on the completion of the colossal original structure.

This Geosite’s name betrays its original purpose. In the 1830s the land adjacent to the site was turned into an enormous gas processing facility. Coal was brought in by canal and later by railway, the site conveniently being at the junction of both, where it would be converted into gas. Enormous gas holders stored it until needed, at which point it was piped away for both domestic and industrial uses in the local area. Locals might remember a successor gas holder that survived on the site until 2007. Sentimentality was apparently absent when two centuries of gas holder history came to an end, with the Stourbridge News quoting a local resident: “It is wonderful it is going as it cast[s] such a shadow over the area”. History failed to record the impression of 19th century Stourbridgians on the completion of the colossal original structure.

During the Second World War, tunnels were dug into the Wildmoor Sandstone to protect workers at the gas works during air raids. It must have been agonizing for those workers nervously waiting in subterranean caverns, illuminated only by candlelight as the sirens blared outside. Had a Luftwaffe bomb struck the gas works, one can’t help thinking that a few metres of sandstone would have offered little protection.

All of this from a small, inconspicuous cliff nestled behind a housing estate. Next time you drive south into Stourbridge, cast your mind back to hippos, mammoths and industry that each, in turn, once occupied this site.

This article was written for BCGS Newsletter 267 by Matthew Sutton.

References and further reading

Bonded warehouse article on gas works:

https://www.thebondedwarehousestourbridge.co.uk/about-us/our-history/a-symphony-for-the-senses/

Stourbridge News – Landmark gas holder is axed:

https://www.stourbridgenews.co.uk/news/1123654.landmark-gas-holder-is-axed/

Amblecote History Society on the gasworks tunnels:

http://amblecote.org/History/AHistory/AirRaidShelters/StourbridgeGasWorks.html

Interglacial fossils paper:

Boulton, W.S., 1917, Mammalian Remains in the Glacial Gravels at Stourbridge. Birmingham Natural History and Philosophical Society Vol XIV Part II, pp.107-112.

Matt’s Maps

The stratigraphic column, map and section have been kindly provided by BCGS member Matt Sutton. (2021)

Black Country Geopark

Stourbridge Old Town Gasworks is one of the Black Country Geopark’s Geosites.