Red House Glass Cone

Early 20th century photograph of the Red House Glass Cone, courtesy of Dudley Museums Service.

Though no rock exposures are visible here, the Cone is one of our region’s geosites and is inextricably linked to the natural resources and geological history that surround it. The Cone, completed around 1790, is the last survivor of more than a dozen glass cones that dotted the Stourbridge landscape along the ‘Crystal Mile’ from the 17th to 20th centuries. Many authors have written at length about the Stourbridge glassmaking industry, which was globally renowned through industrial times. The case here, as with so many other places, is that the story of manufacturing sits atop a much more ancient geological story.

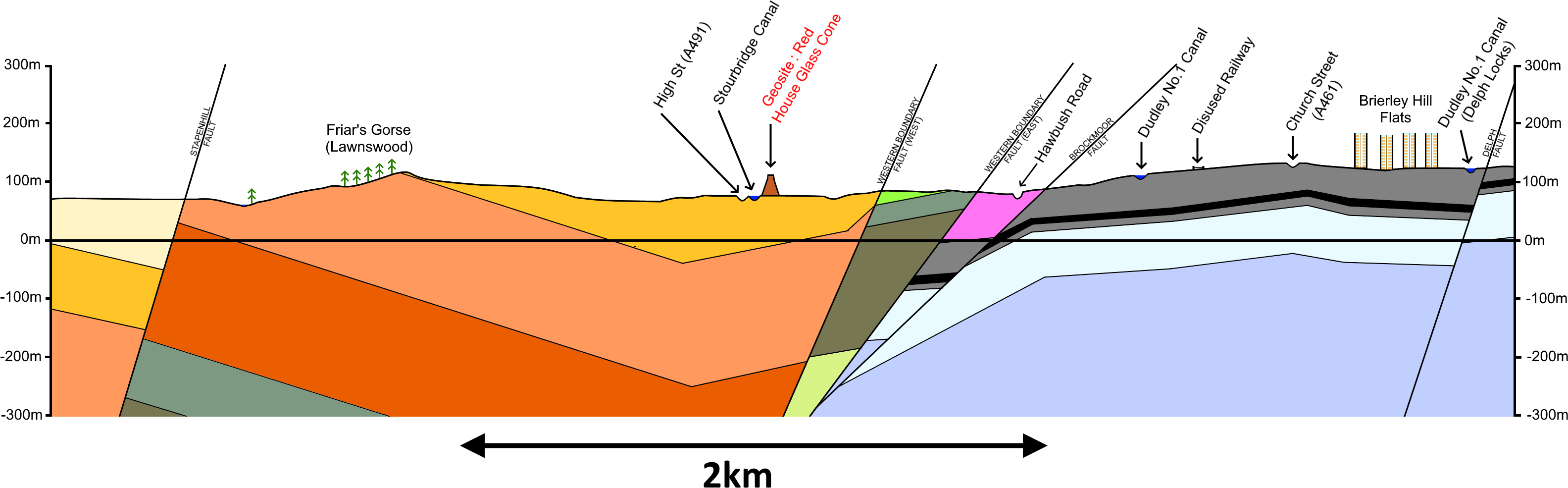

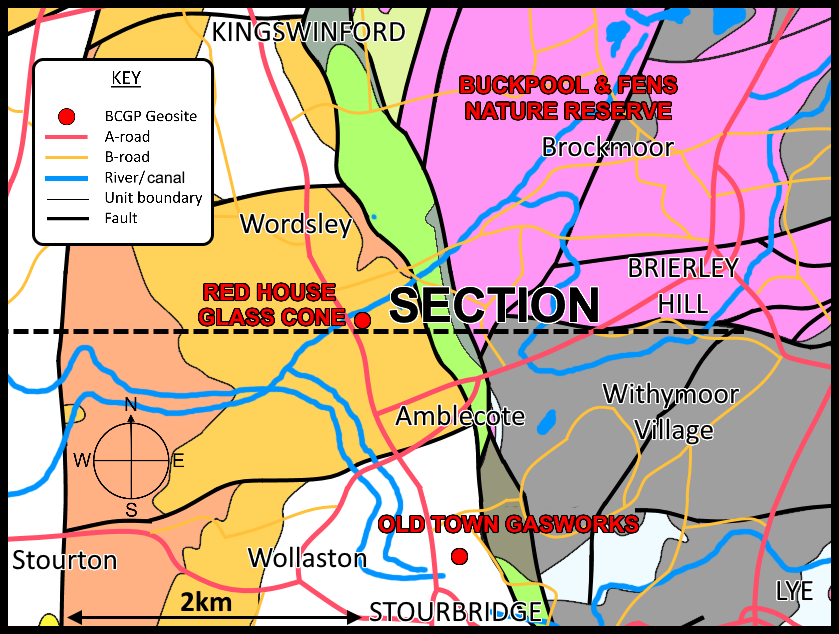

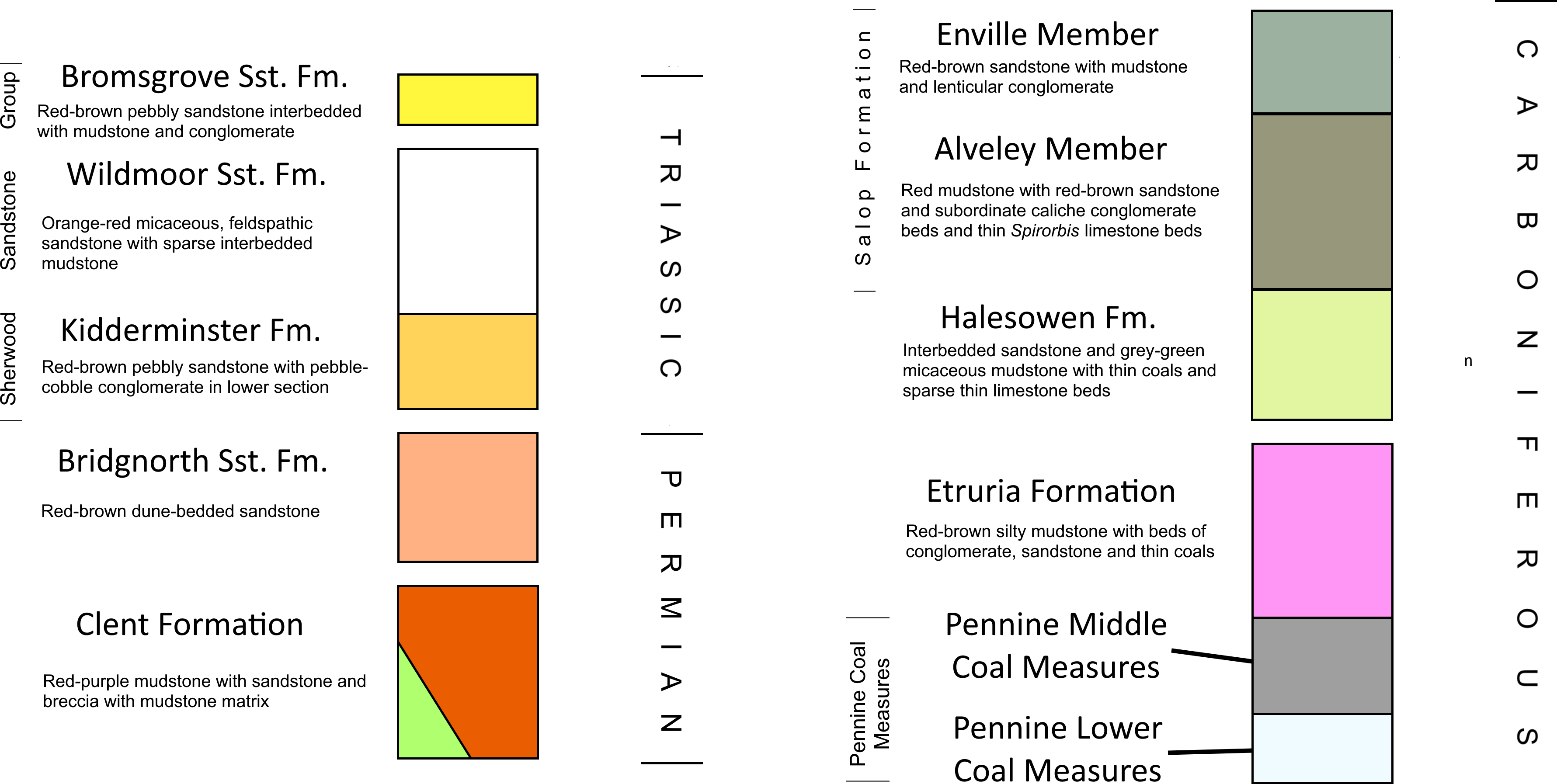

The geology underlying the Glass Cone is very similar to that discussed in Stourbridge Old Town Gasworks, so I won’t go into huge detail here. The Crystal Mile (including the Cone) sits on a Permo-Triassic bedrock of sandstones laid down in the arid interior of the supercontinent Pangaea around 250 million years ago. Uphill to the east, across the coalfield defining Western Boundary Fault, significantly older Carboniferous rocks are thrown up to the surface, exposing a rich mineral tapestry of coals, clays, iron ores and limestones that came to define the Black Country.

Hodgetts, Emily; Glassmaking Scene Inside the Richardson Glass Cone, c.1820; Dudley Museums Service; Oil painting by Emily Jane Hodgetts of the interior of a glass cone as it would have appeared around 1820, reproduced here courtesy of the Dudley Museums Service.

The second thing glassmaking requires is somewhere to make the glass. The cone design is almost as old as the wider Stourbridge glassmaking industry and these structures could accommodate scores of workers. Each work team would work in a ‘glass pot’. Numerous pots would be lined up around the outside of a single large furnace in the centre of the cone. These pots were made from fireclay – an unreactive material that can withstand even the extreme temperatures needed to melt silica.

Glass pots made from Amblecote fireclay. Similar pots would be arranged around the circumference of a furnace in the centre of the Cone, and glass fired inside them. Image from an 1841 manufacturing guidebook and reproduced here courtesy of Birmingham Libraries.

“The most preferable clay of any is that of Amblecote, of a dark blewish colour, whereof they make the best pots for the glasshouses of any in England… The goodness of which clay, and cheapness of coal hereabouts, no doubt has drawn the glasshouses, both for vessels and broad glass, into these parts…”

Lastly, the third vital ingredient you need for glassmaking is a source of energy to generate immense heat for melting sand. Fuel was never in short supply for industrial Black Country folk. There is written evidence of coal mining near Stourbridge as early as 1291, and I needn’t describe in detail here the legacy of coal mining in this region. Many local pits extracted both fireclay and coal in the same locations, whilst others (particularly in the Victorian era) took only the fireclay. The largest glassmaking companies of the 19th century owned not only glassworks, but also fireclay and coal mines.

A final consideration as to how the glassworks ended up in Stourbridge is the location of the town itself. Prior to the late 18th century, exporting any glassware from here would have been hugely hazardous, owing to the lack of a viable waterway connecting it to the outside world. The River Stour was briefly made navigable between 1667-70 before those engineering works were destroyed by flooding. The last piece in the puzzle is surely the opening of the Stourbridge canal in 1779, connecting both the industrial heartlands to the east and the River Severn (via the Staffordshire & Worcestershire Canal) to the west. Barges could now easily transport raw materials to the Crystal Mile and delicate glass products could be safely exported around the country, to the port cities and from there across the seas to the rest of the world. Through a combination of geological good fortune and engineering ingenuity, Stourbridge would thrive as a glassmaking centre for centuries to come.

This cross section is one of three that I created for the 2019 International Festival of Glass in Stourbridge – an annual event co-hosted in the Cone. After a two-year hiatus, the festival will be returning in August 2022. I can thoroughly recommend it to anyone interested in the craft and/or history of glassmaking. Similarly, the new Stourbridge Glass Museum (located directly opposite the Glass Cone) is now open to the public, meaning Dudley Borough’s glass collections will be on public display for the first time in 7 years.

This article was written for BCGS Newsletter 272 by Matthew Sutton.

References and further reading

Emily Hodgett’s oil painting is owned by the Dudley Museums Service. The image and further context can be found at the following link:

https://artuk.org/discover/artworks/glassmaking-scene-inside-the-richardson-glass-cone-c-1820-52472

Glass pots image from The Useful Arts and Manufacturers of Great Britain, Vol.1 (1846).

‘The Stourbridge Fire Clay’, by George Harrison, in (p133): ‘The Resources, Productions and Industrial History of Birmingham and the Midland Hardware District (1865)’, edited by Samuel Timmins. This chapter was an invaluable source of information for me when writing this article, and is available for free online:

https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=nyp.33433087549881&view=1up&seq=153&skin=2021

British Geological Survey factsheet on the economic geology of British fireclays.

https://www2.bgs.ac.uk/mineralsuk/download/planning_factsheets/mpf_fireclay.pdf

Matt’s Maps

The stratigraphic column, map and section have been kindly provided by BCGS member Matt Sutton. (2022)

Black Country Geopark

Red House Glass Cone is one of the Black Country Geopark’s Geosites.