Birmingham Building Stones Trails

References cited in the text are listed at the end of the trail. Hover over words in red (or click if you have no mouse) to see a definition (usually taken from Wikipedia). The stone varieties shown in green in the trail text can be found in our Index of Stones. The index also shows some of the buildings where the stones can be found and gives reference information about the stones.

Trail 1: From the Town Hall to the Cathedral

Birmingham is England’s second city, rising to prominence as an important industrial and manufacturing centre in the 18th and 19th Centuries. It was one of the first of the British urban centres to undergo an industrial revolution, and growing industries brought great prosperity to the city. This led in turn to grand civic buildings, firstly in the Victorian Classical style and later embracing the Gothic Revival and Arts and Crafts movements. This walk introduces the building stones used in the civic centre of Birmingham, from the Classical-style Town Hall to the late 20th Century granite-and-glass office blocks on Colmore Row. Central Birmingham not only presents us with a grand architectural tour of the last 200 years but an accompanying social history in stone.

Unless otherwise cited, all architectural information comes from the Pevsner’s Architectural Guide (Foster, 2007). This is the first part in a three-part series of guides to the building stones of Birmingham City Centre, produced for the Black Country Geological Society.

This walk starts at the Town Hall and takes us through the civic heart of Birmingham in Victoria Square, then heads in a north-easterly direction along Colmore Row, finishing at the Cathedral.

Birmingham’s underlying bedrock is entirely Triassic in age. The NE/SW orientation of the central grid system follows the line of the Birmingham Fault which bisects Birmingham approximately half a mile to the SE of Colmore Row. The higher ground to the NW belongs to the Helsby Sandstone formation (Sherwood Sandstone group), and the lower ground to the Mercia Mudstone group, downthrown to the SE of the Birmingham fault. The civic centre grew up along the solid foundations of the sandstone ridge.

1. Town Hall

Penmon Marble is actually a limestone which is quarried from Penmon Point on the north-east tip of Anglesey. It comes from the Loggerheads Limestone Formation of the Lower Carboniferous (Asbian) Clwyd Limestone Group, (c. 340Ma). These are platform and ramp carbonates, formed in transgressive and regressive cycles. They contain shoals of reef deposits, and fossils are frequently observed in this building; solitary rugose corals include Dibunophyllum sp. and Palaeosmilia sp. as well as colonial corals of Syringopora sp. The rugose coral Lonsdalia floriformis has also been identified. Large, thick-shelled brachiopods, Daviesiella llangollensis are also common. The limestone also shows evidence of bioturbation and is often nodular. Stylolites are also common. These are irregular shaped pressure cracks where mineral material has dissolved reducing the volume of the rock.

The lowermost ten or so foundation courses of the Town Hall, forming the podium, are in rusticated ‘quarry dressed’ blocks with smooth, well dressed masonry above. The building was restored during 2002-2008 with stone sourced from the original quarries. These new, fresh-cut blocks are clearly visible in several places around the building.With the Town Hall on your left, walk a short distance to the centre of Chamberlain Square. The Square re-opened in 2021 after major refurbishment, but the focal point remains the Gothic-style Chamberlain memorial and fountain.

2. Chamberlain Square and Fountain

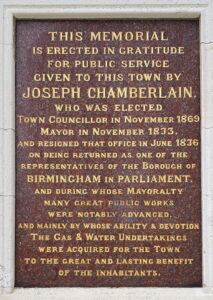

Joseph Chamberlain (1836-1914), was a Liberal politician who began his career as Mayor of Birmingham and then went on to be a Member of Parliament in 1886 in the local St Paul’s Ward. Chamberlain became an influential politician and is also the father of the Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain. The delightful, 20 metres tall, Gothic spire which is the Chamberlain Memorial was erected in 1880 to honour Chamberlain’s public service to the city, and funded by public commission. The monument was designed by namesake, but no relation, John Henry Chamberlain, a follower of John Ruskin and a great promoter of the Gothic Style. The memorial is largely of Portland Stone, the variety called Basebed, thought to be the finest quality of Portland Stone. Although relatively free of fossils, Basebed is slightly less well resistant to weathering and erosion than the more commonly used Whitbed variety. Nevertheless, Basebed is the best stone for taking the fine carving as shown here. Portland Whitbed is used for the lower part of the monument and the coping stones around the pools. These show some dense clusters of fossils, mainly oyster shells. Portland stone is described in more detail in Trail 2, Centenary Square to Brindleyplace. Two of the buttresses have been restored using a light-grey granite which shows evidence of foliation. This is from one of the many granite quarries in Aberdeenshire, most likely Kemnay Quarry to the NW of Aberdeen. The proliferation of monumental granite from Aberdeenshire stems from the mid to late 19th century, when Alexander Macdonald invented a steam-powered method for cutting and polishing granite, thereby speeding up the process, and paving the way for numerous granite businesses. The Aberdeenshire granites were intruded around 470Ma during the Caledonian Orogeny which lasted from around 490-390Ma. Tectonic movements caused continents to collide giving rise to a mountain range comparable with the modern Himalayas. During renovation in 1978, the pools were walled in another light-grey granite. This is Merrivale Granite from Dartmoor. It was formed from the Cornubian batholith which was emplaced during the Variscan Orogeny about 299Ma (late Carboniferous to Early Permian). It contains large white feldspar phenocrysts which distinguishes it from the Kemnay Granite.

The plaque bearing the dedicatory inscription is in a fine piece of coarse-grained red granite, the large brick-red feldspars give this stone its distinct colour. Such granites are sourced from the Kalmar Coast of Sweden and are known as the ‘Coastal Red Granites’. They are derived from a series of 1.4Ga plutons intruded into the Transcandinavian Igneous Belt, part of a major Proterozoic mountain-building phase. The delicate glass mosaics, depicting wild flowers, are by the famous Venetian glass makers and mosaicists, Salviati and Co.

The paving around the monument is a sandstone known in the trade as York Stone. This formed from sandy sediments washed down from mountains to form massive river deltas during the Carboniferous Period around 320Ma. It comes in many varieties from numerous quarries in and around Yorkshire. This robust variety comes from Scout Moor near Bury, Greater Manchester. The colourful concentric lines in many of the paving stones are known as Liesegang bands, a form of staining produced from circulating ground water percolating through the rock.

The 2020-21 refurbishment also brought two foreign granites to the square. The lighter one with prominent white rectangular-shaped feldspar crystals is known in the trade as Alpendurada. It is of Variscan (late Carboniferous) age, and comes from NW Portugal. This is used in the steps and seating. The variegated yellow granite almost certainly comes from Fujian province in China, the source of much of the more recent paving found on these trails. This stone paves the rest of Chamberlain Square, and extends into Victoria Square.

Turn now to the large complex of buildings housing the Council House and the Birmingham Museum & Art Gallery (below).

3. Birmingham Museum & Art Gallery and the Council House

The architect of this suitably impressive civic palace, with its giant Corinthian columns and rusticated walls, was the equally impressively named Yeoville Thomason. The Council House was built between 1874-9 and the Museum and Art Gallery added in 1881-5, following a bequest of paintings from local businessmen, the Tangye Brothers. According to Foster (2007), the Council House and adjacent buildings are built from Coxbench, ‘Wrexham’ and Darley Dale Sandstones. All are Upper Carboniferous sandstones, belonging to the Millstone Grit group (c.320Ma). All three sandstones look incredibly similar and are hard to differentiate when seen out of their geological contexts. All are buff-coloured, quartz-rich, fluvial sandstones, medium to fine-grained and are variably micaceous and cross-bedded.

‘Wrexham Stone’ probably refers to Cefn Stone quarried at nearby Ruabon in Denbighshire (Clwyd). This was a popular stone, widely used for civic architecture in North Wales, the Midlands and the North West of England during the later 19th Century. It is derived from sandstones within the Upper Carboniferous Coal Measures of the North Wales coal field.

Coxbench Stone is from Horsley Castle, Derbyshire. It is a buff-coloured, medium-grained sandstone from the Rough Rock of the Rossendale Formation of the Millstone Grit. Like Cefn Stone it is not well known these days, but was widely used as a building stone in the Midlands and as well as here in Birmingham, it was the main stone used in the construction of Derby.

Darley Dale Stone is more properly called Halldale Stone. Halldale Quarry is situated in Hall Moor Wood, just above the village of Darley Dale where the stone is extracted from a down-faulted outlier of Ashover Grit. The Ashover Grit of the Millstone Grit Supergroup outcrops widely through Derbyshire and surrounding areas and is quarried in many localities, however Darley Dale stone was well known for its homogeneity and durability. The stone was worked here throughout the 18th and 19th Centuries until the quarry closed in the 1960s, however the site was purchased and the quarry reopened by Stancliffe Quarries Ltd. in 1984. Like the rest of the Millstone Grit Group, the Ashover Grits are Upper Carboniferous fluvial sandstones. The strength and homogeneity of this stone give it good properties for carving and it has been used on the Council House for the foliage on the cornices.The pediments are of Portland Stone, most likely the Basebed variety as used in the Chamberlain Memorial. It is a Jurassic limestone (c. 150 Ma) which comes from the Isle of Portland in Dorset, and is widely used for civic and monumental buildings throughout the country. The central pediment facing Victoria Square depicts Britannia rewarding Birmingham manufacturers. Britannia stands 8m tall. (Portland stone will be described in more detail in Part 2 of these building stones tours of Birmingham).

The interiors of the Museum and the Council House feature an impressive range of Devon Marbles, arguably the UK’s most important decorative stone, but sadly no longer worked. The marbles in the interior of the museum, which is readily accessible to the public, have been described in some detail by Walkden (2015b), and the stones he describes are also well illustrated in Walkden (2015a). In British geology the Devonian period is usually associated with red sandstones, deposited in an arid environment, however in the type area of Devon, Devonian strata (c.390Ma) include a series of reefal limestones, deposited in shallow marine conditions and including fossils of corals, stromatoporoids, crinoids and orthocones (shells of extinct nautiloid cephalopods). These were slightly metamorphosed, weakly deformed and stained with iron oxides, to produce the decorative stones we see today. The varieties Red Ogwell, Red Ipplepen, Pink Petitor and dark grey Ashburton Marble are used in the museum. Similar stones are used in the interior of the Council House, though this building is not normally open to the public.

Paving in the entrance porch, Birmingham Museum & Art Gallery

Turn right from the Museum and Art gallery, cross Edmund St. to the imposing Council House extension.

The Council House Extension

This dates from 1908 – 17 and is linked to the Museum and Art gallery by a bridge across Edmund Street. The main structure is composed of a sandstone from the Millstone Grit group in keeping with the original Council House, but stands on a substantial basement of Aberdeen granite from the same Caledonian suite of very varied granites seen elsewhere on this trail. This is a two mica granite from the Aberdeen pluton which is of Caledonian age (c.470Ma). It is most likely Dancing Cairns Granite from a now disused quarry near Bucksburn, a suburb to the NW of Aberdeen.

Walk 1 continues on the next page…

References can be found on the last page of the walk (1.4).